Improving CI Signal

Summary

Our current focus is to aggressively detect payload regressions and use PR reverts to restore payload health. This allows us to keep the organization as a whole moving forward toward a successful release.

Previous state

We were highly susceptible to regressions in the quality of our payloads. This was due to a few factors:

- We couldn’t (too much time, too expensive) run all our CI jobs against all PRs pre-merge, so sometimes we didn’t find out something regressed until after the PR merges

- Even our payload acceptance jobs assume that they will sometimes fail and therefore set the bar at “at least one pass”. This allows changes which make tests less reliable to go undetected as long as we keep getting an occasional pass.

Adverse Impacts

Undetected (or detected but unresolved) regressions in payload health have a number of impacts:

- The longer it takes us to detect it, the harder it is to determine which change introduced the issue because there are more changes to sift through

- Unhealthy payloads can impact the merge rate of PRs across the org as they cause more test failures and generate distraction for engineers trying to determine if their PR has an actual problem

- Consumers of bleeding edge payloads (QE, developers, partners, field teams) can’t get access to the latest code/features if we don’t have recently accepted payloads, so anything that causes more payload rejection to occur impacts our ability to test+verify other unrelated changes

- Unhealthy CI data reduces confidence in test results. Test failures become non-actionable when they become normalized.

- Because all tests must pass in the same job run, we are very limited in which tests we can treat as gating (the tests we gate on must be highly reliable).

With Job Aggregation we now have…

- Faster detection when we regress the health of our payload

- Faster reaction to regressions (either delivering a fix to restore the health immediately, or reverting a change to provide more time to debug)

- Ability to add more semi-reliable tests to our gating bucket and slowly ratchet up their pass rate while ensuring they do not regress further. Our intention is for all nighly payload blocking jobs to be aggregated jobs.

Job Aggregation in a little more detail

Instead of accepting payloads based on a “pass all tests once” gate, an aggregated job allows payloads to be accepted based on running all tests N times and ensures that, statistically, the observed pass percentage of each test is unlikely to have significantly regressed relative to our historical pass rate for each test, unless there is an actual regression present.

Pay special attention to the distinction from previously focus on job success to focus comparing test pass rates within a job to their historical mean. Another important thing to know is that, while these are primarily used for blocking nighly payload promotion, these aggregated jobs can optionally run (pre-merge).

How are they used?

Upon detection of a pass rate regression (As observed via attempted payload acceptance):

- For OpenShift code we find the PR that introduced the regression by opening revert PRs for all PRs that went in since the last good payload and running the payload acceptance check against each revert-PR. The PR that passes the check will tell us which change was the source of the regression. In that case we proceed to revert it and file a bug with the relevant team.

- In rare cases the problem is not in OpenShift but in our underlying operating system. In those cases we’ll work with the CoreOS team to revert the necessary component or even downgrade the OS version.

- If we are not able to clearly isolate the problem, we’ll instead reach out to other teams as needed. For non-blocking situations we may use time on weekly architecture calls for this. More serious situations will result in high severity bugs being filed and at times escalating through management.

- The team(s) owning the bugs or stories are responsible for landing the un-revert along with the fix.

- Un-reverts and fixes will need to pass the same payload acceptance checks before being merged.

What we’re seeing

- Better/faster detection of payload regressions

- We’re able to grow the set of tests used to measure payload health

- Provides a mechanism for teams to pre-merge test their PRs for payload regressions

- Fewer changes to sift through when we do have a regression

- Reduced time to restore payload health (at the cost of more frequently reverting previously merged changes)

- Instead of requiring all tests to pass in the same single run of a job, we can pass as long as each individual test passes a sufficient number of times across all the runs of the job

- This will also allow us to grow the number of CI jobs+tests we use for payload gating

The Mathy/Statistical/Implementation Details

Pass/Fail rates for running jobs 10 times

Using something called Fisher’s Exact Probability Test, it is possible to know how whether a payload being tested is better or worse than the payload(s) which produced a larger dataset. This is the mathy way of finding the statistical thresholds for how many failed testruns should be a failure.

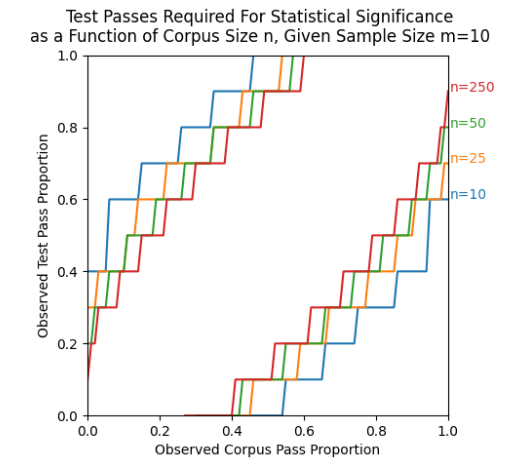

This graph shows us that if the corpus (history) is passing a job,test tuple at 95%, then a payload that only passed 7/10 attempts has a 95% chance of having regressed us.

The lines in the lower right are the number of passes (or less) out of a sample size of 10, required to be 95% sure that the payload being tested is worse than the payload before. We can become more certain by running more iterations per payload or by reducing the threshold for passing.

The lines in the upper left are the number of passes (or more) required to be 95% sure that the payload being tested is better than the payload before. That could be used for faster ratcheting, but for the short term will not be used.

Our corpus/history (n) will be well over 250, so use that line. Our sample size is 10. Find the corpus pass percentage of the job,test tuple. Then go straight up and find the Y value. That value is the pass percent required to be 95% sure that the current payload is worse than the corpus (history).

FAQ

How can I reduce my risk of introducing payload regressions?

If you are making a large change, and are concerned about breaking job flavors that are not covered by your repository’s usual presubmits, consider running /payload ... testing before merging your change.

Who is watching for payload regressions and opening reverts?

For now, the Technical Release Team watches payload results on the current release branch. They will open the revert PRs and engage the involved teams (any team that contributed a PR to the payload that regressed).

How will we be contacted if our PR is part of a regressed payload?

TRT will ping the relevant team slack aliases in #forum-release-oversight.

Who approves the revert for merge?

In order to ensure they are included in the conversation/resolution, we would like the team that delivered the original PR to /approve the reversion. However, if they are unavailable or unresponsive this may be escalated to the staff-engineering team to ensure we do not remain in a regressed state longer than necessary.

What happens if a giant change like a rebase with high business value and on the critical path of the release regresses the pass rate? Will it be reverted? Will we work on it until it passes good enough? What if the kubelet build hours or days later causes the regression?

Since we have a way to run the payload promotion checks before a PR merges, we encourage high risk changes to run the payload acceptance before they merge. If that payload acceptance test fails, then it is 95% likely (math, not gut) that the PR is reducing our reliability. That signal is enough to engage other teams if necessary, but since most repos other than openshift/kubernetes are owned by a single team and that team is the local expert, in the majority of cases the expert should be local.

If the PR isn’t pre-checked and we catch it during payload promotion, then even a high business value PR is subject to reversion. The unrevert PR is the place to talk about expected and observed impact to reliability versus the new feature. Both the revert and the unrevert are human processes, so there is room for discussion.

What does an “identified fix” look like?

To avoid merging the revert, teams will need to be able to point to an open PR that contains a fix, and which has passed the payload acceptance checks.

The payload acceptance check aggregates the result of N runs into a pass/fail percentage and compares it against the baseline. We are going to start by only failing overall when there is a 95% confidence that the PR is worse than the baseline. The exact pass/fail counts vary depending on how bad the baseline is.

We are biased toward passing and only fail when we are 95% confident (mathematically, not gut feel) that the PR is worse than the baseline.

How can we possibly identify a fix before our PR is reverted? Can’t you just give us more time?

Given the timing of these events, it’s understandable that many teams aren’t going to bother investigating if it was their PR that caused the issue until there is definitive proof (in the form of a revert PR that passes the check). And even if they do immediately investigate and open a fix PR, they will be racing against the checks being run against the revert PRs. We will allow some small amount of flexibility here: if the team has a fix PR open, we’ll wait for the check to finish against that PR before merging the revert. But if the checks on the fix PR fail, the team will need to merge the revert and then land the unrevert along with their fix.

Remember, anytime our payloads are regressed, the entire org is being impacted. While there may be a small cost to a single team to land an un-revert, it avoids a greater cost to the org as a whole. We want to get back to green as quickly as possible and avoid a slippery slope of a team wanting to try “one more fix” before we revert. Teams can also optionally run the acceptance checks on their original PR before merging it, to reduce the risk that the PR will have to be reverted.

What if these new checks are wrong?

We will need to carefully study the outcomes of this process to ensure that we are getting value from it (finding actual regressions) and not causing unnecessarily churn (raising revert PRs due to false positives when nothing has actually regressed, or the regression actually happened in an earlier payload but went undetected at the time). TRT will track data on how many times this reversion process gets triggered and the outcomes of each incident and then do a retrospective after the 4.10 release.

What if cloud X has a systemic failure causing tests to fail?

That sort of failure will show up as, “I opened all the reverts and none of them pass”. The relative frequency of this sort of failure is difficult to predict in advance because our current signal lacks sufficient granularity, but it doesn’t appear to be the most common case so far.

What if you revert my feature PR after feature freeze?

We will make an exception to the feature freeze requirements to allow un-reverts(along w/ the necessary fix) to land post feature freeze, even though technically the unrevert is (re)merging a feature PR. Alternatively, consider moving your team to the no-feature-freeze process!

Vocabulary

We often refer to these concepts with an imprecise vernacular, let’s try to codify a couple to make what follows easier to understand.

Job – example: periodic-ci-openshift-release-master-ci-4.9-e2e-gcp-upgrade

Jobs are a description of what set of the environment a cluster is installed into and which Tests will run and how. Jobs have multiple JobRuns associated with them. JobRun – example periodic-ci-openshift-release-master-ci-4.9-e2e-gcp-upgrade #1423633387024814080

JobRuns are each an instance of a Job. They will have N-payloads associated with them (one to install, N to change versions to). JobRuns will have multiple TestRuns associated with them. JobRuns pass when all of their TestRuns also succeed.

TestRun – example [

[sig-node] pods should never transition back to pendingfrom periodic-ci-openshift-release-master-ci-4.9-e2e-gcp-upgrade #1423633387024814080 A TestRun refers to an exact instance of Test for a particular JobRun. At the files-on-disk level, this is represented by a junit-***.xml file which lists a particular testCase. Keep in mind that a single JobRun can have multiple TestRuns for a single Test.Test – example

[sig-node] pods should never transition back to pendingA Test is the bit of code that checks if a particular JobRun is functioning correctly. The same Test can be used by many jobs and the overall pass/fail rates can provide information about the different environments set up by other jobs.Payload Blocking Job – click an instance of 4.9-nightly. About 4 jobs. A job that is run on prospective payloads. If the JobRun does not succeed, the payload is not promoted.

Payload Informing Job – click an instance of 4.9-nightly. About 34 jobs. A job that is run on prospective payloads. If the Job run does not succeed, nothing happens: the payload is promoted anyway.

Flake Rate The percentage of the time that a particular TestRun might fail on a given payload, but may succeed if run a second time on a different (or sometimes the same) cluster. These are often blamed on environmental conditions that result in a cluster-state that impedes success: load, temporary network connectivity failure, other workloads prevent test pod scheduling, etc.